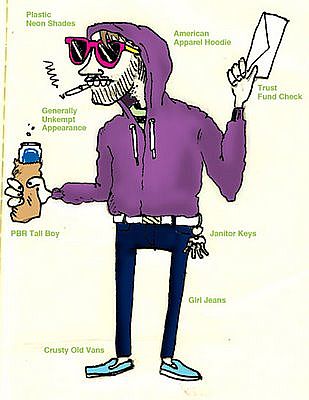

As it's summer time again, an array of music festivals will be/have been taking place around the country. Although I'm probably as far removed from the festival scene as is possible, I still find them rather fascinating in that such events are not only a means to showcase alternative music for a weekend, but also promote a peculiar cultural experience. This experience is constructed from both old ideas oddly reminiscent to that of the 1960's counter-culture movement, as well as concepts more akin to our modern world- particularly the organisational structures built on principles of collective management. I personally believe that this culture has helped to cultivate a rather interesting type of individual, who exists within the myriad of both these old and new ideas. Indeed, I am talking about the modern day 'hipster', and for those of you that don't know, here is a wonderful, satirical picture of such a character;

The 'hipsters' were not, however, always the incarnation they exist in today. In fact, the original 'hipster' subculture developed in America in the late 1940's, and was greeted with the same degree of confusion and cynicism as they are used to currently. The subculture was most prominently examined in Anatole Broyard's essay for the Partisan Review, entitled "A Portrait of the Hipster" published in 1948. Around a decade later, the writer Norman Mailer published "The White Negro" in Dissent magazine. Broyard's analysis focused around the idea of 'superior knowledge' in what he referred to as 'priorism'. He suggested that during the 1940's, ethnic minority communities, though particularly the African-American communities, were the 'subject to decision' of power structures they were unable to engage with. As almost a mechanism of defence, these communities would act, verbally and symbolically, on forms of their own 'prior' understandings. Broyard focuses on the actions and symbolic gestures that early hipsters had created as means of articulating such forms of understanding. Meanwhile, Mailer's essay presented the idea of the 'hipster' as a reactionary sub-culture, that looked away from politics to ascertain their identity. While the African-American community had constructed an identity through a similar method, as a response to racial opression, the young bohemians had simply adopted these techniques to form a self serving, individualist agenda,;

"The hipster had absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro, and for practical purposes could be considered a white Negro."

In both essays, the hipsters were characterised as a reactionary subculture, subdued by the power structures they existed within. But while Broyard's analysis saw the emergence of the hipster as a cause built on ideas of racial conciousness, I feel that Mailer better captured the sociological aspects of this peculiar culture, illustrating how the formulation of an 'outsider culture' developed through the means of individualist resistance, and articulated itself in the forms of material agency. But, just as the African-Americans they seemed to be imitating, this cultural generation sought to emancipate themselves from what they perceived as old, institutionalist political structures that they felt only served only to dominate them.

It was the capturing of the new sensibility, that found itself at the ideological heart of the 1960's student movements. However, while the movements we are used to witnessing today are very much economic (at least in the West, anyway), the movements of the sixties and seventies had a much more complex, cultural undertone. It was also within these movements, that many students in both the United States and Europe harnessed ideas similar to that of Broyard and Mailer to voice their discontent.

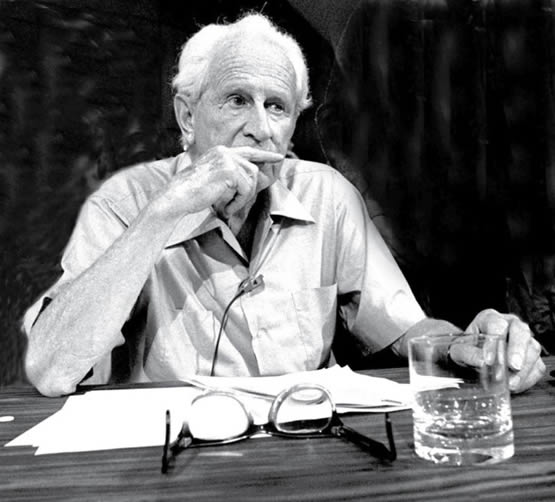

Herbert Marcuse was a prominent academic and intellectual, whose ideas are most closely associated with the 'New Left' movement- a movement whose birth was very much the product of post-war anxiety, and a discontent with the USSR as an ideological base. In 1964, he published "One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society". In the book, he argued against traditional Marxist orthodoxy, by claiming that in advanced industrial economies, the revolutionary capacity of the industrial proletariat had significantly diminished. Instead, the economy would work to 'stabilise' these individuals by integrating them within the existing system of production, and by the creation of false, material needs. He went on to argue that this type of structure would cultivate a 'one-dimensional' environment, where the capacity for dissent and opposition would be drastically diminished. But one of the most important observations Marcuse made, was simply that the consumerist culture had worked to recondition people's social lives and by extension, their social conciousness. Being aware of the Freudian ideas that had dominated the 20th century, 'One Dimensional Man' had then also presented the idea that Freudian psychological ideas had also contributed to the repressive system embodied within advanced industrialist economies, in that they assisted both the state and corporations in social domination.

In today's understanding of the Hipster culture, I feel that both Anatole Broyard and Norman Mailer

still remain relevant, in that they ultimately highlight how much identity is related to materiality. In the twentieth century, the 'hipster' culture was used as a means of resistance, against a system that was seen to dominate individuals. As such, the early hipsters harnessed individualism through material objects to express both opposition and liberation. Yet, it would be difficult to attribute such values to the type of hipsters who frequent music festivals. What is interesting, however, is how the modern understanding of hipster culture is understood. Devoid of any political basis as their counterparts were blessed with, the modern hipster seems to instead reflect the victory of advanced industrial societies, in that they are now defined more by a culture that is influenced significantly by consumerist ideals. Instead of being a cultural force of opposition against systematic production, the modern hipsters have ironically become a part of it.