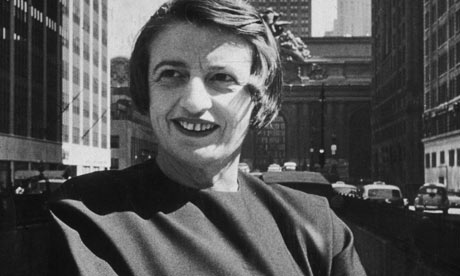

On the surface, Ryan shouldn't really be that interesting. In fact, he's a rather boring economics nerd, hailed as the 'intellectual figurehead' of the GOP- a humorous, yet also disturbing title to be ordained with, considering the present state of the party. Yet, in this electoral season, the ' Ryan plan' , seems to be serving various goals. Firstly, to assist in repositioning the electoral narrative, shifting focus away from personality politics to one based primarily on economic strategy. The second objective, is much more interesting, In a semi-religious fashion, the plan has, in an almost biblical way, resurrected a rather peculiar character of the late twentieth century- one whose philosophical presence has permeated into American politics on more than one occasion. This entity, is Ayn Rand.

Rand had escaped Soviet Russia in 1926, settling instead, for New York city. She worked intially as a screenwriter for many popular 'epic films' , while simultaneously writing her own fiction. In 1957, She wrote her most famous novel- the one in which Paul Ryan has claimed to gain much of his inspiration- Atlas Shrugged. It was also the novel that framed her peculiar, but oddly popular philosophy- one that espoused the virtues of elitism- not only by justifying the presence of elites in society, but also suggesting that they were necessary for any society to flourish. In the Randian view, these elites, or in her words, the 'prime movers' should be cherished by society, as their presence subsequently gave a more profound meaning to one's life, than that of the state or it's bureaucrats. The philosophical foundation of the Randian world view, was what she referred to as 'Objectivism'. Here is an interesting video, where she explains this philosophy;

While Paul Ryan has insisted that Rand's novels serve only as a source of inspiration relating to policy, there is a startling degree of complexity woven within her narratives. In fact, the free market rhetoric that forms the basis of Randian-inspired ideology within the current GOP, serves merely as a simplistic, if not superficial interpretation of her body of work. Although Rand certainly believed in such ideals, her novels are probably more useful in illustrating the exercise of power within the Randian world, and how her objectivist philosophy does not simply manifest itself within the market economy, but as an extension, forms the basis of human relationships. Indeed, both her famous novels, The Foutainhead and Atlas Shrugged not only reject moral frameworks that do not encompass the self, but also illustrate the triumphs of objectivism in its confrontation with other philosophies. Through physical action and material manifestations, fantastical worlds are constructed within both the novels; The Foutainhead follows the 'prime mover' Howard Roark's relentless defence of his artistic integrity and vision, against the tyrannical bureaucrats. Atlas Shrugged further conveys these principles through the protagonist and model prime-mover, John Galt. In response to the oppression of the state against the 'prime movers', Galt organises the exodus of the other prime movers (creatives, financiers and other such elites), as a means not to create the Randian world elsewhere, but rather, and in a rather peculiar, masochistic fashion, watch society erode in absence of the elites. The 'moral' (if one would continue to use this term) of the story however, has less to do with the evils of big government (as the GOP and other such conservatives seem to have interpreted) than the nature of the Randian universe itself. The order of this environment does not lie in the notion of 'free and equal individuals', but rather, an understanding that elites in society, the 'prime-movers' occupy an elevated status that must be exempt from any attempted form of moral regulation. Furthermore, as these elites endow onto wider society, a successful model of organising and distribution, they are also granted the right to 'protect' and 'regulate' those that are lesser than them. Thus, it seems to be the case that the Randian world is far from Paul Ryan's libertarian utopia- instead, it proposes a different organisation of society whereby the prime movers are granted legitimacy, simply on the basis that they are superior beings.

How this superiority is acquired, seems less to do with economics than a peculiar, Randian understanding of power- which are depicted in the characterisation of her 'heroes'. The Fountainhead sees the architect, Roark as the sole defender of his vision for a skyscraper, against the bulwark of 'mediocrity', who in Roark's eyes, exists only to compromise his creativity. Yet more often than not, one fails in the attempt to interpret the nature of Roark's vision itself. What are the components of the fantasy, which make it absolute? In this case, I'd argue that Roark's vision does not simply embody a creative idea for a building. Rather, it embodies a constructed fantasy as an extension of himself; In accepting this compromise, Roark would not only gives up the sky scraper in it's material form, but also his own individuality,all to what Rand describes as the parastic system, designed specifically to restrict the 'prime mover'. Roark, the Randian hero, finds himself existing it a nightmare world, but one in which he must retain his integrity to survive. Similarly, the exploration of power in Atlas Shrugged also centres around an assumed dominance of the 'prime-movers', although more explicity directed toward government and bureaucrats. The chants of 'Who is John Galt?' that embody street slogans, also allude to the metaphysical notion of the self. In this case, Galt, the Randian hero, elucidates not only a man superior in practical purpose (ie. in terms of organisation and physical rebellion), but similarly acts as symbolic of 'power' itself, within the Randian universe. As such, Galt's organised rebellion effectively removes the life-source of society, rendering it helpless and pathetic, left only with the failed parental state, destroyed by the virtues of collectivism and egalitarianism. The novel ends with the return of the 'prime-movers', the true parental figureheads of the society, and with whom natural order is restored. Ultimately, Rand shows us that it is these movers that have constructed the world for the benefit of lesser mortals, and as such, can just as easily dismantle, or re-build it in their image- and with a greater degree of perceived legitimacy.

More interestingly, what of the psychological, or rather, the psycho-sexual dimensions within the Randian world? It seems to me, that in our examination of Rand today, commentators look too much toward her ideas of moral economy, and in this case, taking the position that 'self-interest' being the only rational mode of existence, is somewhat incomplete. For it is in examining human behaviour itself, that Rand forms the basis of her peculiar philosophy, and nowhere is this more evident than in sexual conduct. Yet, not so long ago, the now notorious philosopher, Slavoj Zizek, wrote a paper in the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies examining her body of work through this very approach. In the paper, Zizek argued that the 'Randian world' was somewhat representative of a pure capitalism, without the sugar-coated pills offered by the evils of government. In this pure world, the Randian heroes, or the prime movers, would occupy a position somewhat innocent of the evils such sugar-coated pills assist in developing; thus, Roarke's uncomprimising stance on his creative integrity can only be seen as a moral good, because man himself is working toward the greatest good he can internally occupy. Roarke requires no recognition from others to make moral judgements on his actions, possibly for the sole reason that such external judgements hold little meaning. Such an idea might be best analysed through this clip of The Fountainhead motion picture;In this case, I feel that Zizek has probably come closest in accurately depicting the 'Randian hero' has much more than simply an economic prime mover. While conservative Randians may view Roarke and Galt as ultimate justification of free market capitalism (effectively becoming ideological commodities), Zizek instead exposes their innermost drives, making clear that the need to satisfy their internal desires can make them capable of the very things the Radian hero is supposed to be devoid of- in this case, love for the other. In Atlas Shrugged, the removal of the 'prime movers' brings about the erosion of the harmonious, industrial society. The movers make clear that the 'other' are dependent on them, and thus occupy a more powerful position when they return. Yet, why do the prime movers return back to the society that rejected them? The prodigal sons here, do not return with sorrow and repentance, but rather, with triumph- and a 'love' for the other. It may be the case that just as the other is dependent on the prime mover to survive, the legitimacy of the mover is subsequently concentrated on the acquired legitimacy of the other. A distinction, however, does remain in place- while the mover's motivation lies in the drive for self satisfaction, the 'other' is driven by a desire for the mover. No more is this better illustrated than in a particular scene of The Fountainhead, where the dialectic between Roark and Domonique are explored. Domonique is characterised as the 'other', consumed only by a desire for Roark, whilst Roark, driven only by his vision, views Domonique only as a means to settle temporary satisfaction, all of it being completely unattached from emotions. For Rand, notions of sex were not simply that of emotional engagement, but were rather based on rational values and principles; If extended to the rape scene in The Fountainhead, one might suggest that Roark is both fulfilling his primal, temporary urges, as well as re-inforcing the paradigm of the Randian world, whereby as a prime mover, he occupied a position where he may overpower Domonique, with the latter's full compliance. Meanwhile, if Domonique was to have a meaningful relationship with Roark, she must 'transition from desire to drive', adapting her value system to fit within the Randian understanding of the rational world- one in which sexual action acts as a means to fulfil rational, individual needs, as well as to maintain it's established, hierarchical tenants.

Such analyses as that of Zizek, show just how complex Rand actually is. Those that adore her,mainly tend to see her too much as a prophet of the free-market cause, preferring to ignore the depth of human exploration necessary to achieve such aims. Indeed, Rand shows that particular psychological conditions have to be in place for the rational, free market to remain in place- much of which challenges general understandings of morality today. Yet similarly, those that dismiss her ideas, may also be short sighted. While Rand believed heavily in the objectivist ideology, it might be the case that even she misappropriated the philosophical tenants behind her ideas, which when applied outside the economic sphere, appear contradictory. Whether Paul Ryan has really thought about Rand in such depth, I'm not sure, but I suppose that might be the reason why her resurrection was fairly short-lived.

No comments:

Post a Comment